Changing Your Mind with Mindfulness Meditation, Part 2

Neuronal Plasticity, Mindfulness Meditation, and Addiction Recovery

by Nicholas A. Nelson, Ph.D.

Part 2 of 2

In Part 1, we visited the motivations for leveraging mindfulness as a tool for overcoming problematic addictive behaviors. We discussed the concept of neuroplasticity and took a theoretical look at how mindfulness meditation can aid in reshaping our brain and behavior during addiction recovery.

In Part 2 we’ll take a look at a few specific scientific studies that have put these theories to the test, then wrap up with a discussion of what mindfulness meditation can feel like in practice. Let’s dive in.

The Frontal Lobe

Because the neuroscience of addiction and neuroscience of meditation are rather complex and relatively new topics, they are still undergoing rapid developments as new ideas and technologies become more popular. Still, some foundational ideas are beginning to really take root. In the context of addiction and meditation, we’ll focus on these foundational findings within one main brain region: the frontal lobe.

The frontal lobe is located towards our forehead just behind the eyes and can be broken into numerous subregions, each of which contributes to different aspects of our cognition. In general, these frontal lobe regions control a group of cognitive skills known as “executive functions” – the ability for us to act as intelligent, thoughtful executives of our minds and behaviors. Executive functions include things like the ability to consider risks and rewards, make long term plans, focus our attention onto a single task, or temper our emotional responses.

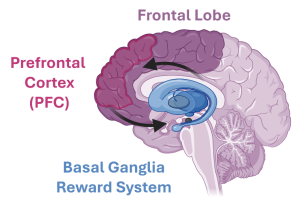

Parts of the frontal lobe – especially within the prefrontal cortex (PFC), a key region for the control of executive functions – decrease in activity through the course of addiction. This is especially true during the experience of withdrawals [1,2]. This means that, at a neurological level, the ability of a person to utilize their executive functions is significantly disrupted during established addiction. More plainly: Addiction and withdrawal actively decrease the function of brain regions responsible for our ability to make intelligent decisions.

While it is true (and important) that the brains’ reward circuitry is also heavily perturbed in the course of addiction, we’re focusing on the frontal lobe here for a reason: reward circuitry receives significant input from these frontal lobe regions. Typically, the desire to pursue a reward from something like drugs can be balanced by the frontal lobe: the brain’s reward circuitry may be actively trying to seek out a strong reward from a drug or behavior, but the frontal lobe can turn down the intensity of this urge, acting as a sort of brake system. Our executive functions might calculate probable risks vs. rewards, consider alternative courses of action, or recognize that an urge is just an urge and not something that must be acted on. While it is true that reward circuitry is considerably altered during the development of addiction, its problems are fueled in no small part by the lack of control that results from an underactive frontal lobe.

Figure 1: Illustration of brain circuitry impacted by both addiction and mindfulness training. The frontal lobe (purple), especially a region called the prefrontal cortex (PFC, magenta), both sends and receives information from deeper brain regions like the basal ganglia (blue) as part of the reward system.

It stands to reason then that strengthening frontal lobe connectivity could help decrease the tricks a dysregulated reward system tries to play on us.

The other motivation for focusing on the frontal lobe and executive functions here is because these are precisely the skills that mindfulness practices seek to invigorate.

Executive Function Training

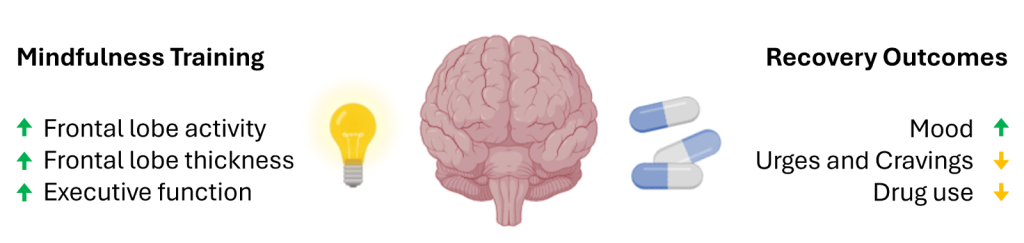

In modern psychological terms, mindfulness practices can be viewed as a form of “executive function training.” Accordingly, numerous studies have investigated the impact of mindfulness practices on frontal lobe regions responsible for our executive functions.

When studied in real-time by fMRI, researchers observe high levels of activity in numerous frontal lobe regions during focus-based meditation practices compared to activity levels at rest [3]. Additionally, structural brain scans of individuals with a long-term meditation practice find that frontal lobe regions are significantly larger relative to control populations [4,5].

The principles of neuroplasticity predict that repeated behaviors and mental habits will, through time, lead to changes in the architecture of our brain circuitry. Real-time studies demonstrate that brain regions controlling executive functions can be activated by mindfulness practice – so we know that mindfulness practice is targeting the regions we hope to strengthen during addiction recovery. Studies on long-term meditators show that this real-time activity is also reflected in lasting structural changes to the brain – namely, the brain regions controlling executive functions grow with long-term practice.

Thus, mindfulness meditation changes frontal lobe activity patterns both now and into the future – precisely what we would predict from the principles of neuroplasticity, and precisely what we are looking for in building new mental habits during addiction recovery.

Studies on Mindfulness Based Practices for Addiction

While the above studies focused on frontal lobe regions in volunteers without addictive problems, the frontal lobe regions identified overlap considerably with regions that become underactive during the development of addiction. Researchers are therefore beginning to put mindfulness practices to the test in addiction recovery, with some notable success.

In addiction studies, scientists measure numerous outcomes with each experiment – things like the strength of urges and cravings, drug/behavior abstinence, mood (sometimes called affect), and so on. Not every study measures all of the same things, and not every study finds impacts of mindfulness on every variable measured. This is to say there is variability in what outcomes are observed and variability in what is even measured.

That said, one consistent finding is a significant reduction in urges and cravings as a result of mindfulness-based practices [6]. Some studies show incredible benefits across numerous measures, like a study of 154 volunteers undergoing opioid use treatment, where significant improvements in drug use frequency, depression, adherence to medical treatment, and even pain levels during drug discontinuation were all observed [7]. Some also measure real-time brain activity, with one study in cigarette smokers measuring activity levels while showing participants videos intended to cause nicotine cravings. Following mindfulness training, they find both a reduction in reward circuit misfunction and increased activity in the frontal lobe in response to these nicotine cues [8].

I mention these specific studies to highlight two points: 1) When looking at behavior of people in mindfulness-based recovery practices, we can see a reduction in drug abuse behaviors and self-reported negative feelings during abstinence, and 2) when looking at brain activity directly, we can see a strengthening of frontal lobe activity and normalization of the reward circuitry downstream of it.

Taken altogether, we are seeing measurable neurological changes and corresponding behavioral changes, in a positive direction, as a result of mindfulness training during addiction recovery.

Ongoing Work

As mentioned, this research is still relatively young and constantly developing. Different studies use different mindfulness “treatments” – some just encourage mindfulness meditation, some actively challenge participants with exercises meant to induce cravings, others have entire meditation courses and protocols for participants to follow. The studies are also heavily biased towards nicotine and opiate users – not necessarily because meditation works better for these addictions, but likely because these populations more frequently agree to enroll in studies.

While mindfulness has shown benefits across multiple domains of recovery and can be a meaningful, accessible tool for many, it is not a cure-all, nor is it necessarily the right fit for everyone. Recovery is highly individual—what works for one person, or even many, may not work for all.

What is particularly promising, though, is that many of the neurological features shared across addiction types – such as an underactive frontal lobe and dysregulated reward circuitry – appear to be directly impacted by mindfulness practice. That the intensity and frequency of urges and cravings are consistently reduced by mindfulness is also notably important: urges and cravings are common to all types of addiction, and are one of the most difficult impediments people face during recovery.

Even as research continues to evolve, early evidence strongly suggests that mindfulness-based approaches may enhance executive function in ways that directly support recovery. And while mindfulness alone is not a cure-all, a growing body of evidence supports its role as a valuable tool in the recovery process for many people.

Incorporating Mindfulness

To wrap up this two part series, we’ll move away from science and data and more into the practical application of mindfulness practice.

There are dozens, if not hundreds, of ways to cultivate mindfulness. I do want to preemptively say there is no wrong way to build mindfulness – for some people it is a deeply religious practice, for some it is a completely secular training and exploration of their mind. Some people want to incorporate feelings of love and gratitude, some people want to build a laser sharp focus with nothing in their head. These are all fine – it is worth exploring these options with an open mind, finding what works for you and discarding the things that don’t quite click.

And while I say there is no wrong way to build mindfulness, there is a right way: with the intention of building that 1) non-judgemental 2) awareness of thoughts and feelings, 3) focused in the present moment. Find the route that builds those three things that works well for you.

Being More Mindful During Recovery

I want to conclude by sharing what this brain training feels like in practice.

First, there’s the part that is a bit subconscious and subtle. You may make a few decisions 0.01 seconds faster than usual, or think a touch more clearly when presented with a difficult problem. Anxiety and depression don’t just disappear, but they may feel a shade less overwhelming, little by little. You won’t immediately stop having cravings, but through time you may notice they are less common, or less intense when they occur. This is the slow process of neuronal plasticity in effect – you are strengthening your executive functions, and they slowly, subtly build new automatic responses. Little by little. This takes time and the change is gradual. But with consistent practice, it grows. Slowly and steadily. One day a clearer mind and milder, less-frequent cravings just become… normal.

Second, the option to be mindful in daily life begins to show up more regularly. You will still encounter difficult situations. You will still encounter urges and cravings, your personal relationships will have ups and downs, you will still be stuck at a traffic light because the person in front of you was driving too slow. You will still have emotional reactions to the world around you.

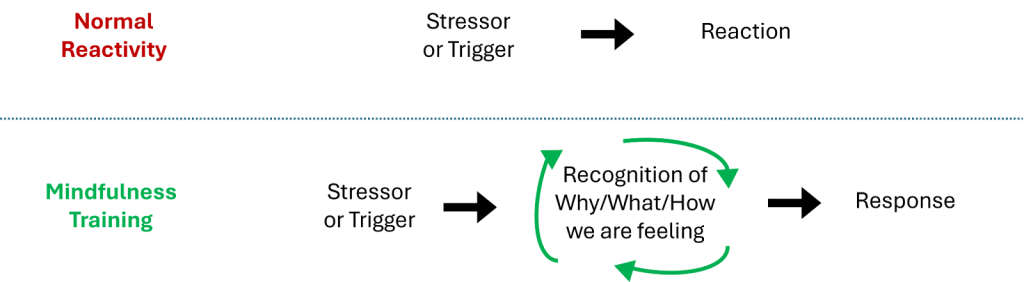

What mindfulness builds for us is a small space between our stressors and our responses to them. We get used to having a non-judgemental awareness of our thoughts and feelings. This awareness is where some serious benefits can take hold – if we choose to let them.

Figure 3: Illustration of where the practice of mindfulness creates space, to more deeply consider our responses to the emotional situations encountered in our daily lives.

Finding Space

A favorite meditation teacher of mine likes to share a story of a young man who would come to his meditation groups for college students:

The college student came to the teacher and said “Hey, I think I get how this meditation stuff is supposed to work.”

“That’s great man, what did you notice?” the teacher responds.

“Well I was at a party, and I saw a dude talking to my girlfriend. I was pissed, I wanted to kick his ass. But I realized I was angry, and I didn’t have to act on it.”

“That’s beautiful. So what did you do?” the teacher asks his star pupil.

“Well, I punched him in the face.”

This is normally met with laughter, but is also met with praise! This is what early success looks like. Cultivating a mindfulness practice gave the student space to notice that he had other options.

I love this story in the context of addiction because, like every other approach to addiction recovery, mindfulness is not a quick fix for our problematic behaviors. It does train our frontal lobes. It does increase our ability to think clearly. It does temper our impulsive reactions.

But impulses and emotions are a part of life, they occur no matter how strong the frontal lobe is. The practice of mindfulness will build our ability to recognize, in the moment, that we are experiencing an emotional reaction. While it can show us the space between a stressor and our reaction to it – like it did for our college student above – it is still up to us to change our behaviors in the face of urges, cravings, and other strong emotions.

This aspect makes mindfulness a fantastic complement, a fantastic addition, to other recovery approaches. Mindfulness can help us recognize where we have a decision in how to react. Active engagement with recovery can give us the tools to know which type of reactions best fit with our goals and values.

Mindfulness can show us the door. When and how we walk through it is still up to us.

Final Thoughts

If and how you integrate mindfulness into your life is up to you.

My recommendation is to build a daily habit. Start small, with something you can reasonably promise yourself you will do for a week or two straight. Mindfulness works best when practiced regularly, even if it is only for 5 minutes per day. Neuroplasticity builds through repetition, so finding a consistent habit is key.

Guidance from a teacher can be extremely useful. This is easily done by searching YouTube, or through meditation apps like Insight Timer, Headspace, Calm, or Waking Up (there are many more, often with free trials).

There are recovery programs that focus on mindfulness, and many recovery programs have mindfulness-focused meetings within them. Web search with keywords like “mindfulness” or “meditation” and your preferred recovery program can help you locate these. The same can be said for individual therapy – meditation and mindfulness training is an increasingly common skillset for therapists, and your existing therapist/healthcare provider may have recommendations even if they don’t practice mindfulness themselves.

There are also meditation classes and groups held by both religious and secular organizations. I meditate on my own nearly every day, and despite being minimally religiously-inclined, I find tremendous benefit in attending a Buddhist temple for a group meditation weekly. I found what works for me. I found what helps me build the kind of mind I want to inhabit. This was not what I initially thought would work for me (indeed, it initially would not have worked for me), but through gradual exploration I’ve built a meditation practice as a cornerstone of my cognitive health.

Try a few approaches and see what seems to work well. Find what works for you – whatever form it may take. And as with all things recovery-related, recognize your successes and progress (big or small), explore it with curiosity and grace should you stumble, and cultivate what works for you while you leave the rest.

Missed Part 1 of Mindfulness Meditation? Read it here!

Acknowledgements and References for Part 2:

Figures 1 and 2 were made using resources from BioRender.com

[1] Goldstein RZ, Volkow ND. Drug addiction and its underlying neurobiological basis: neuroimaging evidence for the involvement of the frontal cortex. Am J Psychiatry. 2002 Oct;159(10):1642-52. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1642. PMID: 12359667; PMCID: PMC1201373.

[2] Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurobiology of addiction: a neurocircuitry analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016 Aug;3(8):760-773. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00104-8. PMID: 27475769; PMCID: PMC6135092.

[3] Wang DJ, Rao H, Korczykowski M, Wintering N, Pluta J, Khalsa DS, Newberg AB. Cerebral blood flow changes associated with different meditation practices and perceived depth of meditation. Psychiatry Res. 2011 Jan 30;191(1):60-7. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.09.011. Epub 2010 Dec 8. PMID: 21145215.

[4] Kang DH, Jo HJ, Jung WH, Kim SH, Jung YH, Choi CH, Lee US, An SC, Jang JH, Kwon JS. The effect of meditation on brain structure: cortical thickness mapping and diffusion tensor imaging. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2013 Jan;8(1):27-33. doi: 10.1093/scan/nss056. Epub 2012 May 7. PMID: 22569185; PMCID: PMC3541490.

[5] Luders E, Toga AW, Lepore N, Gaser C. The underlying anatomical correlates of long-term meditation: larger hippocampal and frontal volumes of gray matter. Neuroimage. 2009 Apr 15;45(3):672-8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.12.061. PMID: 19280691; PMCID: PMC3184843.

[6] Garland EL, Howard MO. Mindfulness-based treatment of addiction: current state of the field and envisioning the next wave of research. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2018 Apr 18;13(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s13722-018-0115-3. PMID: 29669599; PMCID: PMC5907295.

[7] Cooperman NA, Lu SE, Hanley AW, Puvananayagam T, Dooley-Budsock P, Kline A, Garland EL. Telehealth Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement vs Usual Care in Individuals With Opioid Use Disorder and Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2024 Apr 1;81(4):338-346. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.5138. PMID: 38061786; PMCID: PMC10704342.

[8] Froeliger B, Mathew AR, McConnell PA, Eichberg C, Saladin ME, Carpenter MJ, Garland EL. Restructuring Reward Mechanisms in Nicotine Addiction: A Pilot fMRI Study of Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement for Cigarette Smokers. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2017;2017:7018014. doi: 10.1155/2017/7018014. Epub 2017 Mar 8. PMID: 28373890; PMCID: PMC5360937.