Can a Single Episode of Extreme Binge Drinking Change the Brain?

by Kenneth Anderson, MA

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) defines binge drinking as drinking enough alcohol to reach a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of 0.08% or higher, i.e., to become legally intoxicated. For men, this typically means drinking five or more US standard drinks in a two-hour period. For women, this is typically four or more standard drinks in a two-hour period.

Extreme binge drinking, also known as high-intensity drinking, is defined as drinking enough alcohol to achieve a BAC of .16% or higher, in other words, drinking twice as much as the amount for regular binge drinking. Extreme binge drinking is associated with throwing up or passing out. In the United States, extreme binge drinking is a common occurrence at 21st birthday celebrations, which is when one achieves legal drinking age. “Twenty-one drinks on your 21st birthday” has become a common saying in the US.

Hua et al. (2020) conducted a study to see whether engaging in a single episode of extreme binge drinking at a 21st birthday celebration could cause changes in the brain. There were 78 subjects about to celebrate their 21st birthdays who were recruited at the University of Missouri who completed the initial evaluation, which consisted of an MRI scan of their brains an average of 11 days before their birthdays; nearly all subjects were college students, although a few non-students were evaluated as well. Fifty of these 78 students completed the second part of the study, which consisted of an MRI scan of their brains three to four days after their 21st birthdays. 29 subjects completed the third part of the study, which consisted of an MRI scan of their brains five weeks after their 21st birthdays.

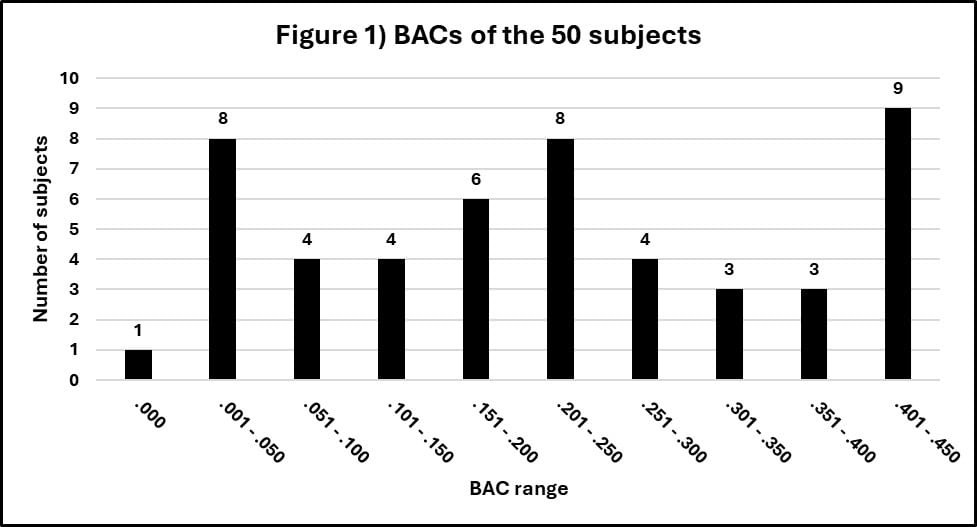

The subjects attained an average peak BAC of .22 during their 21st birthday celebrations, ranging from .0 to .45. The peak BACs per subject are shown in Figure 1. One subject didn’t drink at all, and nine subjects exceeded .40%

The researchers measured the effect of extreme binge drinking on the corpus callosum to see if there was any effect on its volume. The corpus callosum is the large tract of neurons in the middle of the brain which connects the right hemisphere to the left hemisphere, allowing signals to be transmitted from one hemisphere to the other. The researchers were interested in the corpus callosum because many previous studies had shown that heavy drinking affects the volume of the corpus callosum. The researchers looked to see if there were changes in the front part of the corpus callosum, the central part or the rear part. What they found was a significant effect of the quantity of alcohol consumed on the volume of the rear part of the corpus callosum: the higher the subject’s BAC, the lower the volume of the rear part of the corpus callosum. Additionally, subjects who had alcoholic blackouts during their 21st birthday celebrations showed significantly more volume loss in the rear part of the corpus callosum than those who did not have blackouts. The reduction in the volume of the rear part of the corpus callosum was still present at the five-week followup. The rear part of the corpus callosum is involved in visuospatial information transfer, language, reading, calculation, IQ, behavior, and consciousness. It is important to bear in mind that the brains of 21-year-olds are still developing, hence, this study does not allow us to draw conclusions about the effects of a single episode of binge drinking in older adults.

There were no significant effects of a single episode of extreme binge drinking on the front or central parts of the corpus callosum. The researchers also looked at the hippocampus (the seat of memory) and the orbitofrontal cortex (the seat of decision making); however, there was no significant effect of a single episode of extreme binge drinking on either of these two areas. The researchers also looked to see if a single episode of binge drinking led to any changes in the folds (gyrification) on the surface of the brain. There were no significant effects of a single episode of extreme binge drinking on gyrification.

Using this same data set, Boness et al. (2019) looked to see if a single episode of extreme binge drinking led to microstructural white matter damage in the corpus callosum and the fornix (a bundle of white matter which serves as the output tract of the hippocampus). The researchers used a method called diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) to look for microstructural white matter damage. Diffusion tensor imaging measures the movement of water molecules; this movement is expressed with a variable named fractional anisotropy (FA). Simply put, if the movement of the water molecules is completely random (Brownian motion), the value of FA is 0. An example of this is a glass of water; the molecules in a glass of water move completely at random. If the water molecules are all moving in the same direction, such as water flowing through a pipe, the value of FA is 1.

The white matter of the brain is comprised of neurons which have a myelin sheath around their axon. Myelin is a fat-like substance which is 40% water. When the myelin sheath is intact, the water tends to flow along the length of the axon. When the myelin sheath is damaged, the water moves more at random, and the value of FA is lower. The normal value of FA varies greatly depending on which white matter tract one is looking at: for the rear part of the corpus callosum it is about .78.

Although the researchers initially believed that they had found evidence of microstructural white matter changes, this paper was later retracted because there had been a mix up in the data. So, we do not have evidence that a single episode of extreme binge drinking damages white matter in 21-year-olds. Although it may seem contradictory, it is quite possible to have a reduction in the volume of white matter without a change in the integrity of white matter. That is what we appear to have in this case.

In conclusion, a single episode of extreme binge drinking can lead to volume loss in the rear part of the corpus callosum, and this volume loss persists for at least five weeks. How much longer it might persist is currently unknown. Does this loss of volume mean that a single episode of binge drinking has killed brain cells? Probably not. As discussed in a previous blog post, brain shrinkage is a common result of heavy drinking which is reversed with abstinence from alcohol.