Nixon, Reagan, and the War on Drugs

By Kenneth Anderson

All too often I hear people erroneously lay the blame for the current war on drugs on Nixon; however, this is historically inaccurate. The focus of Nixon’s war on drugs was treatment, and under Nixon, the harsh drug laws of the 1950s were eased. Ronald Reagan was the true architect of the evil known as today’s war on drugs. Let’s start by looking at some historical background.

The US Rise of Substance Use

The US Rise of Substance Use

There was an explosive growth in the use of marijuana from 1967 to 1979, with LSD bringing up the rear. Although marijuana and LSD were promoted in the early 1960s by both Timothy Leary at Harvard and Ken Kesey at his ranch in rural La Honda, California, about 42 miles from San Francisco, their influence was quite local and had little impact on the US as a whole until the late 1960s. Even the 1967 Summer of Love was still a regional phenomenon. The first data on the prevalence of marijuana and LSD was a Gallup Poll published in the November 1967 issue of Reader’s Digest which found that only 6% of US college students had ever tried marijuana, and less than 1% had tried LSD.

Ironically, a major factor in the growth in popularity of these drugs may well have been the media scare stories intended to warn people against using them, such as the March 25, 1966 LSD cover story in Life magazine, a two-part story in the May 21 and June 4, 1966 issues of the Saturday Evening Post titled “Drugs on Campus,” and the revival of the TV series Dragnet on January 12, 1967 with the series premiere episode “The LSD Story.” Marijuana and LSD were also featured in exploitation films such as The Trip (1967), Something Weird (1967), and Easy Rider (1969). LSD was legal throughout the US until 1966 when it was banned by state laws in Nevada and California. It was banned by federal law in 1968 (Pub. L. 90-639).

A 1969 Gallup Poll found that 22% of US college students had tried marijuana, 4% had tried LSD, and 10% had tried barbiturates. It was also found that 4% of all adults over 21 had tried marijuana. A 1970 Gallup Poll found that 42% of US college students had tried marijuana, 14% had tried LSD, 15% had tried barbiturates, and 16% had tried amphetamines. By 1971, the numbers had increased to 51% of US college students for marijuana, 18% for LSD, 15% for barbiturates, 22% for amphetamines, 7% for cocaine, and 2% for heroin.

The US government finally started tracking drug use in 1971, first through the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse (aka the Shafer Commission), then in 1974 through the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Marijuana use peaked in 1979; NIDA’s National Survey on Drug Abuse for 1979 stated that 29.95% of US residents over the age of 12 had used marijuana at least once in their lifetime, and 8.55% had used LSD/hallucinogens. In the past year, 18.08% had used marijuana, and 2.81% had used LSD/hallucinogens.

When we break this down by age groups, in 1979, 30.9% of 12-to-17-year-olds had ever used marijuana, and 7.1% had ever used LSD/hallucinogens. For 18-to 25-year-olds, 68.2% had ever used marijuana, and 25.1% had ever used LSD/hallucinogens. For those aged 26 and older, 19.6% had ever used marijuana, and 4.5% had ever used LSD/hallucinogens.

Past year use in 1979 was as follows: 24.1% of 12-to-17-year-olds had used marijuana in the past year, and 4.7% had used LSD/hallucinogens; 46.9% of 18-to 25-year-olds had used marijuana in the past year, and 9.9% had used LSD/hallucinogens; and 9.0% of those age 26 and older had used marijuana in the past year, and 0.6% had used LSD/hallucinogens.

Nixon and the War on Drugs

Before the late 1960s, the marijuana laws primarily affected black and brown people because very few white people used marijuana. From the late 1960s on, the overwhelming majority of people using marijuana were white. Marijuana laws before the Nixon era were harsher than those during the Nixon era, for example, the Narcotic Control Act of 1956 (Pub. L. 84-728) carried a mandatory minimum of two years in prison for simple possession of marijuana and allowed for the death penalty for the sale of heroin to minors. However, this had gone unnoticed so long as few white people were being arrested.

Nixon’s war on drugs was all about the expansion of the US addiction treatment system. The Special Action Office for Drug Abuse Prevention (SAODAP) was in operation from June 17, 1971, to June 30, 1975. Under SAODAP, the number of patients in federally supported addiction treatment programs increased from 16,000 to 82,000 between 1972 and 1974, and in 1974, community drug treatment programs were treating 160,000 patients, 130,000 of whom were being treated for opioid dependence. The number of cities with federally funded drug treatment programs increased from 54 to 214 in the first 18 months that SAODAP was in operation. The greatest expansion was in increasing the availability of methadone maintenance; in 1974, of the 130,000 people who were being treated for opioid dependence, approximately 60% were in methadone maintenance, 4% were in detoxification treatment, and 36% were in drug-free treatment, such as therapeutic communities.

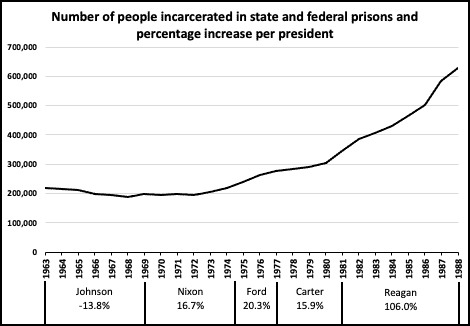

Moreover, the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970 (Pub. L. 91-513) eliminated the mandatory minimum sentences and death penalty of the Narcotic Control Act of 1956. During the five and a half years Nixon was in office, the number of prisoners in state and federal prisons increased by a modest 16.7%.

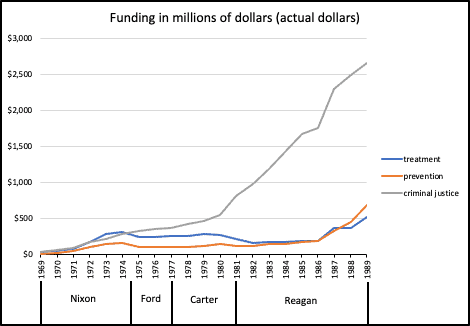

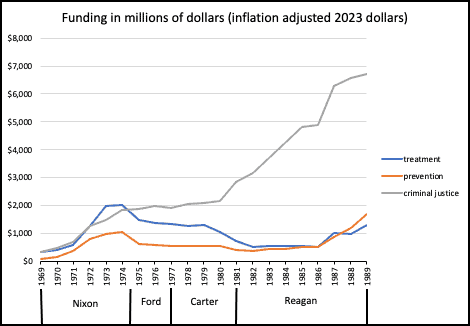

Nixon resigned on August 9, 1974, and SAODAP ended on June 30, 1975. Under Nixon, more money had been spent on drug treatment than on criminal justice responses to drug use. Under Ford and Carter, this was reversed, the budget for treatment was cut and the budget for criminal justice expanded, as is shown in the following charts (data from Treating Drug Problems, Volume One).

The chart to the right shows the number of people incarcerated in state and federal prisons from the Johnson era to the Reagan era and the percentage of increase or decrease under each president (data from Historical Statistics on Prisoners in State and Federal Institutions, Yearend 1925-86, etc.). The prisoner census is from December 31 of the previous year, which is only 20 days prior to the presidential inauguration dates on January 20.

The chart to the right shows the number of people incarcerated in state and federal prisons from the Johnson era to the Reagan era and the percentage of increase or decrease under each president (data from Historical Statistics on Prisoners in State and Federal Institutions, Yearend 1925-86, etc.). The prisoner census is from December 31 of the previous year, which is only 20 days prior to the presidential inauguration dates on January 20.

The Drug War Under Ford and Carter

No major or unexpected changes occurred under the Ford and Carter administrations. Ford was inaugurated on August 9, 1974, the day that Nixon resigned. SAODAP ended on June 30, 1975, as scheduled in the legislation which created it. SAODAP’s treatment and prevention efforts were transferred to NIDA as planned, and its criminal justice component was transferred to the DEA. NIDA’s treatment contracts were converted to grants around this time. In 1975, federal funding for treatment dropped to $250 million per year, and federal funding for criminal justice responses to drugs increased to $320 million per year. This was the first time since 1971 that criminal justice responses were funded more highly than treatment. The number of people incarcerated in state and federal prisons increased by about 20% during the two-and-a-half years that Ford was in office.

Carter was inaugurated on January 20, 1977. Funding for treatment remained fairly steady under Carter in nominal dollars, although, because of high rates of inflation, the buying power of these dollars was less. Funding for criminal justice responses to drugs increased from $370 million in 1977 to $810 million in 1981. The number of people incarcerated in state and federal prisons increased 15.9% during the four years that Carter was in office. Although Carter stated that he favored decriminalization of marijuana in an August 2, 1977 speech to Congress, he did nothing to back his words up with actions.

Reagan and His Role in the War on Drugs

Reagan was inaugurated on January 20, 1980. Reagan more than doubled the number of people incarcerated in state and federal prisons during his eight years in office. One of the first things that took place under the Reagan administration was the passage of the 577-page-long Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1981 (PL 97-35) on August 13, 1981. Under Ford and Carter, the grants to and contracts with local drug treatment providers had been managed by NIDA after SAODAP had closed. Likewise, the grants to and contracts with local alcohol treatment providers had been managed by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). Under the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act, all this money was bundled together with mental health money and given to the states as alcohol, drug abuse, and mental health block grants for each state to spend as it saw fit. Moreover, the funding was cut by 25%. NIDA and NIAAA were taken out of the treatment business entirely and relegated to doing nothing but research. The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act also largely dismantled the welfare state, leaving impoverished inner-city dwellers with few opportunities to survive other than by selling drugs, and helping to spur on the development of the so-called “crack epidemic.”

Reagan’s next move was the passage of the 363-page-long Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 1984 (Pub. L. 98-473) on October 12, 1984, which included increased federal penalties for the cultivation, possession, or transfer of marijuana.

Reagan’s 193-page long Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 (Pub. L. 99-570) became law on October 27, 1986. This law included a five-year mandatory minimum for distribution of 5 grams of crack cocaine or 500 grams of powder cocaine (the notorious crack-sentencing disparity), a study on the use of existing federal buildings as prisons, and the Crack House Statute, which continues to be used to block safe injection facilities today.

Reagan’s 365-page long Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988 (Pub. L. 100-690) became law on November 18, 1988. This law included a five-year mandatory minimum for mere possession of 5 grams of crack cocaine or 500 grams of powder cocaine (the 1986 law had been for distribution). This law also reinstated the federal death penalty for certain drug-related crimes (state-level death penalties had been reinstated by the Supreme Court in 1976). This law also established the Office of National Drug Control Policy.

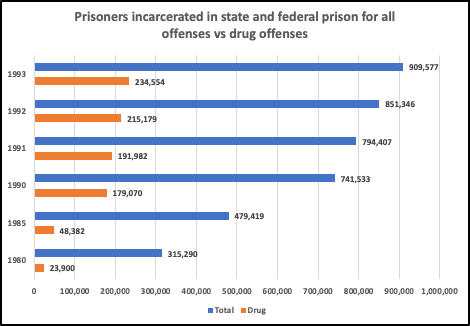

There are no good data available on incarceration by type of offense prior to 1980. The chart here shows the number of people incarcerated for all offenses and those incarcerated for drug offenses from 1980 to 1983.

There are no good data available on incarceration by type of offense prior to 1980. The chart here shows the number of people incarcerated for all offenses and those incarcerated for drug offenses from 1980 to 1983.

The percentage of people incarcerated for drug offenses increased from 7.6% of all prisoners in 1980 to 25.8% of all prisoners in 1993.

So, it is an error to blame Nixon for the current war on drugs. Nixon’s war on drugs was focused on drug treatment and Nixon could be nicknamed “the methadone president.” Reagan’s war on drugs, on the other hand, focused on increasing incarceration and decreasing treatment. Reagan should really go down in history as “the mass-incarceration president.”

Liked this article? You might also be interested in: America Celebrates the Drug War’s 50th Anniversary